When I was little I visited the UN General Assembly auditorium in New York City. This experience left its mark. Historical and beautifully-designed podia built to inspire, mark excellence, and foster communication and debate became my thing.

In March 2011 following an invitation by the Department of Health to chair, co-author and contribute as an executive board member to a programme of work focussing on Early Diagnosis in Dementia, it never occurred to me that two years later I’d be co-presenting our findings at such an architectural landmark.

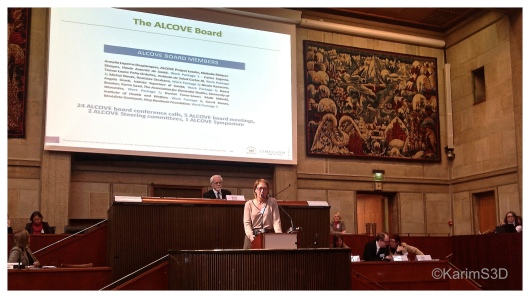

The launch of the ALzheimer’s COoperative Valuation in Europe (ALCOVE) joint action, an EU clinical network incorporating 30 partners from 19 EU Member States, punctuated by an early morning press conference,

took place at the impressive Palais d’Iéna, built in 1937, now a protected historical monument and the HQ of the Economic, Social and Environmental Council in the heart of Paris.

A final three-day event in Paris preceded the launch. Executive board members planned deliberated and rehearsed the final hours, including the last minute recording of eleven ALCOVE videos. The pace was frantic.

On Thursday the 28th March 2013 Professor Dawn Brooker (Director of the Association for Dementia Studies) and I presented the UK findings alongside guest collaborator Professor Anders Wimo (Karolinska Institute, Sweden).

Also in our delegation were Jenny La Fontaine & Jennifer Bray (our brilliant researchers, Association for Dementia Studies), Jerry Bird (National Dementia Strategy, Department of Health) and Peter Ashley, (person living with dementia, honorary Masters Degree, University of Worcester). An international audience included delegates from 24 countries. Speakers included

· Jean-Paul DELEVOYE, President of the French Economical, Social and Environmental Council

· Jean-Luc HAROUSSEAU, President of the French National Authority for Health

· Michael HÜBEL, Head of Programmes & Knowledge management, Health & Consumers DG, European Commission

· Alistair BURNS, National Clinical Director for Dementia, United Kingdom

· Michèle DELAUNAY, French Minister of the Elderly and the Autonomy

Together with the final synthesis report (108 pages) and the full list of recommendations (10 pages) you can capture our main headlines.

Inspired by Egypt’s pyramids, our recommendations on Timely Diagnosis incorporated an incremental strategy to dementia healthcare planning across the EU and within member states.

An approach that will interest all those working in the field, tackling as they do some of the most challenging issues facing health and social care, including the ethics of early diagnosis.

We hope to present the findings and associated reports in the UK throughout this coming year.

ALCOVE has enabled us an unprecedented glimpse of the status of dementia services across Europe. To me the Paris launch combined excellence in design with new advances in science. A fitting rite of passage!

As the globe wakes up to the impact of dementia, it is my belief that this launch will prove as historical as the Palais d’Iéna.

@KarimS3D